Fences

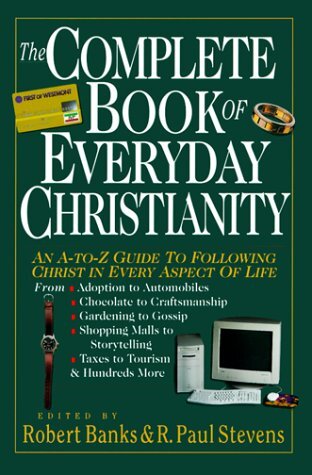

Book / Produced by partner of TOW

The word fence conjures up both negative and positive reactions. A popular song of the past that echoes a common turn of phrase, “Don’t Fence Me In,” reveals our preference for having plenty of space around us. We do not like to be hemmed in by restrictive boundaries. Though both the phrase and the song had their origins in life on the range in the American West, the sentiments they contain are shared by the majority of people in newer Western societies. Are fences a prerequisite for being good neighbors, or do they destroy community?

On the positive side, fences became necessary to protect animals and crops, even in the American West. People who live in towns or cities usually want to erect fences around their properties. There are interesting national differences here. For example, in the United States fences tend to be lower than elsewhere and are generally set up around the line of the house and back of the property, not along the sides of the front yard or between it and the street. This approach is now being imitated more frequently elsewhere.

All kinds of practical reasons are given for having fences. First, they keep children and pets within bounds. True, but if we had a more communal way of life, others could also keep an eye on children and animals. Second, fences also help prevent the wrong kind of intrusions upon our living arrangements by nosy neighbors. This is also understandable, but both intrusions and nosy neighbors might be partially handled in other ways, such as the design of the house. Third, fences enable us to develop our own particular landscape and gardens. Yes, but this can largely be done through the proper siting of trees, shrubs, beds and so on.

Often it is not the fact of a fence that is problematic; it is its size and extent. The basic difficulty is that our attitude toward fences betrays an inherent ambivalence. As much as the song mentioned above captures our desire for freedom, our properties express our desire for privacy. These apparently contradictory tendencies have a common root, namely, our desire for independence. We want to be free to go wherever we want and free from the demands of others. In the United States, at least, settling for fences around the back parts of people’s homes may be a way of saying to others, “You can have some access to the public part of me, the part that I present to the world, but not to the private part of me hidden from sight.” In other words, it is a sign of both openness and resistance to community.

The front yard is a form of transitional or semicommunal space: others are free to enter it, but there is no guarantee they will be welcomed into the private space of the house or at its rear. When a front yard is completely fenced off, the owners are sending a clear signal that this property has nothing to do with the wider community. If fences on any part of the property are too high for casual conversation, the owners are indicating that they do not want much contact with neighbors. Some have experienced what happens when a fence between neighbors has to be torn down and replaced: for a time contact increases and a sense of community builds, but this ends abruptly the moment the new fence is up.

With respect to fences there are three main options before us. One is to look for properties that put them in their proper place, serving necessary physical functions without curtailing significant social ones. Another is to reduce the height and extent of fences on our existing property. A third is to go into a cooperative housing complex where there are open grounds between residences that can be used by all those who live around them and lend themselves to regular communal gatherings.

» See also: Community

» See also: Home

» See also: Neighborhood

References and Resources

J. Solomon, The Signs of Our Time: Semiotics—The Hidden Messages of Environments, Objects and Cultural Images (Los Angeles: Tarcher, 1988).

—Robert Banks