Games

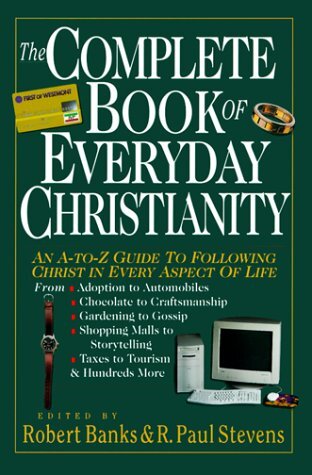

Book / Produced by partner of TOW

Games are like complex toys that people can play, provided they know how and will obey the rules. Games can engage people fully. Each player at the checkerboard is there as a whole person, focused on playing. Games are bona fide, God-given invitations to be playful and therefore can open people to God.

God Enjoys Play

Whether the voice of Wisdom in Proverbs represents the Holy Spirit or Jesus Christ, it is striking that Wisdom was playing before God’s face at the creation of the world, having fun (Proverbs 8:31; meshaheqeth JB). God’s wild beasts and Leviathan also frolic in creation (Job 40:20; Psalm 104:24-26). Integral to the promise of the Lord’s restoration of God’s people as caretakers of creation on the new earth is that boys and girls shall be able to play in the streets without getting hurt (Isaiah 11:6-9; Zech. 8:1-8).

In the here and now joy is the primal gift of the Holy Spirit to those who receive the gift of salvation (Galatians 5:22-23; 1 Thes. 1:2-7). Thus sourpuss Christianity is certainly out of line with the God of the Bible and the communion of saints. Joy, however, is deeper than pleasure, for there is in jubilation a more outgoing, imaginative character than the satisfaction of merely being pleased. So joy, fun and glad exuberance are the normative traits of playing around and therefore form the clue to the meaning of games.

A Game Is Organized Play

Babies and children play in sandboxes or at the seashore, let mud ooze through their toes and laugh as the waves make them happy with God’s slap of wetness. Grownups are often playful in a caress with their loved ones or indulge in wordplay, like puns. There is always an element of surprise in playing, such as the wonderful excitement experienced when riding a swing hung from the branch of a tree. This unpredictable element epitomizes play and other aspects of the ludic dimension of life. So playfulness explores the unexpected ambiguity that inheres all human activity and sometimes comes to the fore, especially in games.

More complex than simple play, games always have rules and usually demand a certain amount of skill from those who participate. Further, everything in the game happens in the realm of a make-believe reality. The players have to imagine somebody as “it” to play tag and must decide whether or not a player can tag back immediately upon becoming “it.” Games thrive on uncertainty and usually involve some kind of guessing on what to do next. Should you aim for the wicket in your croquet shot or knock somebody else’s ball into the rough? Every player strives to reach the end or goal of the game first, even though the elusive prize is imaginary. A great thing about games is that everyone, technically, begins evenly, and that evenness is recovered every time the game is restarted. So children can occasionally win over their parents, and the stronger may lose to the weaker thanks to the wonderful uncertainty that always goes with a real game, such as when the marble or bocce ball just happens to hit a piece of uneven ground. A game to its players is very close to what Wonderland was for Alice: During a player’s turn in jumping rope, reciting limericks while jumping up and down, he or she can cheerfully have the illusion of being a prima donna. And children play the hunter and the hunted in kick the can with shivers of expectation and tables turned. Good games always carry the aura of adventure.

Do Games Have a Purpose?

Educators have long understood that children learn through playing games and that play is work for a nursery school child. So games serve a social purpose. Games that last are much more complex than any one person and have been shaped by societal milieux, historical circumstances and the faith perspective of cultural communities. Anthropologists have noted, for example, that Inuit children of the Canadian North played games of physical skill that fostered memory, rather than games of chance and strategy. Inuit childhood games were thus congruent with a harsh, subsistent life and world in which the young were nurtured to do their best but not at the expense of others. The games of the Iroquois in the New York area were more competitive athletic contests, tied to rites invoking rain or ceremonial dances for the blessing of fertility on the crops—matters outside human hands.

Naturalistic psychologist Karl Groos (1861-1946) interpreted games to be a kind of animal survival-kit practice that the young exercise to rehearse coping with adult activities. Pragmatist educator-theorist Jean Piaget (1896-1980) traced the development of games played by children (sensory-motor, then make-believe, finally symbolic games with rules) and found they geared very strictly to stages of a child’s preverbal and postverbal accommodation and socialization toward external reality. Games for Piaget are indices of human maturation; full-grown, well-adjusted humans outgrow them. And many a Christian moralist has excused games only if they help Christians take themselves less seriously or help them work more efficiently afterward: Learn to relax and lose—it’s good for you. Enjoy games as pleasant lessons in humility, perhaps even as a foretaste of a heaven free from drudgery.

A biblically directed conception of games will take us beyond the mere instrumental value of games. We should not miss the peculiar glory and blessing built into the play that God created us to enjoy, and we should not apologetically twist games into becoming a means for nonplayful ends. It is true that games generally help us discharge pent-up surplus energy, aggressive and otherwise, and games do prepare us to exercise competencies in nonthreatening situations—strength, agility, decisiveness or willingness not to be a poor loser. But games need to be reconceived as a diaconal service for mature people through which they thank God as the games invigorate the players’ imagination. Games are not something particularly childish or remedial, nor are they a middle-class luxury or a waste of time. The refusal to play games or the indulgence in a life of constant game playing—each is an indication of an imbalanced and unhealthy spirituality.

The Rich Variety of Games in God’s World

There are many, many games for children and adults to play. Within the rough taxonomy that follows the games appear in order of their complexity, with the most elementary appearing first:

basic movement and control (kite flying, roller-skating, swimming, bicycling, skiing, gymnastics)

testing physical properties (making mud pies, molding clay, sawing wood)

chase and capture and lost and found (hide-and-seek, blindman’s buff, fishing, hunting)

display (dressing up, participating in parades)

skill competence (catching a ball, spinning tops, shooting marbles, horseshoes, quoits, darts, group juggling, spelling bees)

guessing (Who am I? charades, Pictionary)

puzzles (fitting shapes in holes, jigsaw pictures, crosswords, anagrams, Scrabble)

get-acquainted (passing grapefruit from neck to neck, forming group tableaux)

chance (dominoes, card games, board games with dice, mahjong)

combative strategy (checkers, chess, tennis, squash, pickup team sports)

trust-relationships (blind fall and catch, Balderdash)

sheer pretense (masquerade party)

One can turn almost any fascination or activity that has flair into a game so long as there is an obstacle to overcome or something whimsical that eludes straightforward calculation and implementation. There is much to be said for inventing our own games. Games that are no longer homemade but are standardized and manufactured, as with board games, remove to arm’s length the congealed play of a homespun game. Boxed games are like secondary sources, and one needs to be wary of the imported spirit hidden in the prefabricated game. Is the game inherently ruthless (the Darwinian Monopoly)? fact-ridden (Trivial Pursuit)? ingenuous (Authors)? fantastically extravagant (Dungeons and Dragons)? During the 1960s there was a rise in noncompetitive group games, such as “mixers” made up for occasional social gatherings (see The New Games Book and More New Games), which were wholesomely critical of the overly intense, win-at-all-costs mentality that followed World War II and hurts genuine play. Computer games also are a mixed blessing, as they teach us to interact with a machine in a socially isolated context.

Games of chance, such as card games or games with dice, have often been stigmatized by Christians as evil pastimes (or been co-opted by the church for charitable purposes—for example, bingo). Rather than approach games of chance as a violation of belief in God’s providence, or suppose that the element of chance is playing loosely with God’s will, we should view hidden cards in bridge and unpredictable dice as simply a handy way to bring the play in reality to the fore. Picking up six vowels and only one consonant during a turn in Scrabble or throwing a double six so you land on a penalty square in a board game is “accidental,” but the chance draw or throw calls upon all your human ingenuity to achieve more with less—precisely the imaginative challenge amid the laughable surprises of any game. And God sees the ludic crux of games and says, “It is good!”

When Games Go Bad

Game theorist Roger Caillois (1913-1978) puts his analytic finger correctly on what corrupts games: when the very real boundary of imagination that defines their terrain and structure is violated, the play of players and games is ruined (Caillois, pp. 43-55). Godless indulgence in sportive amusement that is licentious and idolatrous is clearly wrong (Exodus 32:1-6; 1 Cor. 10:6-13). Further, games themselves can be denatured. To cheat at hopscotch or even to play marbles for keeps is to end the playfulness. Gambling is always the murder of a game, because gambling violates the allusive play of the God-created game world and enslaves fun in the straitjacket of mammon. Lotteries are an illicit turn to games even if they be legal tender.

Video games are mechanized, with a built-in drive for speed and power, which augurs poorly for leisure and harbors an imaginative, consumerized violence that is the antithesis of personal relaxation. A dubious quality of computerized virtual-reality games is their conjuring of decorporealized illusions that appear more real than ordinary imaginative reality, in which one enjoys throwing Frisbees or boomerangs and knows the laughter of touching bony backs in a game of leapfrog. To call professional sports a game is a misnomer. The gladiatorial contests of professional sports worldwide bank on the thrill of God’s ludic gift and honed acrobatic human skill, but in our days, so close in temper to those of Noah (Matthew 24:36-44), professional sports have corporately adulterated the game element into an abnormal, fascinating play-for-pay spectacle, as beautiful as an expensive cancer.

Redeeming the Time by Playing Games

Game opportunities bear a redemptive slant when they awaken and stretch the players’ imagination to rejoice in the miraculous surprises God has created for us to experience together. The best games may not be those one can become ever more skilled at, sharpening the competitive edge, but those that most generously spread around communal good humor and a refreshing playfulness based on feeling at home in God’s world despite the secularized brutalization of all things bright and beautiful. Games that lean toward bonding younger and older generations in good fun, that tickle smiles to the faces of those who have been abused or wasted, that cement friendship because the playing time, you remember afterward, was as holy as good prayer—such games, many still to be invented by the saints, carry a coefficient of the Lord God’s grace and offset both an obsession with pleasure and a workaholic mania. When Christ returns, one could do worse than be found with an orphan visiting a zoo of God’s fantastic animals or playing checkers with a lonely widow or widower in a deserted convalescent home, letting them be imaginatively useful and take initiative in joyfully jumping your king. There will be no games in hell, only ennui.

» See also: Imagination

» See also: Leisure

» See also: Play

» See also: Recreation

» See also: Sabbath

References and Resources

J. Byl, “Coming to Terms with Play, Game, Sport and Athletics,” in Christianity and Leisure: Issues in a Pluralistic Society, ed. P. Heintzman, G. Van Andel and T. Visker (Sioux Center, Iowa: Dordt College Press, 1994); R. Caillois, Man, Play and Games, trans. M. Barash (New York: Schocken, 1979); A. Fluegelman, More New Games (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1981); A. Fluegelman, The New Games Book (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1976); B. Frey, W. Ingram, T. McWhertor and W. D. Romanowski, At Work and Play, Biblical Insight to Daily Obedience (Jordan Station, Ont.: Paideia Press, 1986); J. Piaget, pt. 2 of “Play,” in Play, Dreams and Imitation in Childhood, trans. C. Gattegno and F. M. Hodgson (New York: Norton, 1962); H. B. Schwartzman, Play and Culture, vol. 4 of the proceedings of the annual meeting of the Association for the Anthropological Study of Play (West Point, N.Y.: Leisure Press, 1980); T. Visker, “Play, Game and Sport in a Reformed Biblical Worldview,” in Christianity and Leisure: Issues in a Pluralistic Society, ed. P. Heintzman, G. Van Andel and T. Visker (Sioux Center, Iowa: Dordt College Press, 1994).

—Calvin Seerveld