External Materials Hosted by TOW Project

Article /

A Theology of Work for a Post Industrial Age

Back to Table of Contents Back to Table of ContentsBy Rev’d Dr. Kenneth J. Barnes, Dean of the Marketplace Institute, Ridley College, Melbourne, Australia

In his collected papers entitled, Reflections on Non-stipendiary Ministry As Ministry in Secular Employment (1989-96), Dr. James Francis of the University of Sunderland states quite succinctly the paradoxical nature of work as both blessing and curse in the Bible. In an article entitled, God as Worker: A Metaphor from Daily Life in Biblical Perspective, Dr. Francis notes,

In so far as work forms a major and essential part of human life it is to be expected that the modeling of the transcendent in religious discourse will in some way reflect the idea of God as himself a worker, if not (as in Biblical perspective) the Worker par excellence. In the metaphorical understanding of God in the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament there is a projection (and perhaps a discernment) concerning the value and significance of work. That projection and that discernment relate to the subjective awareness of work as toil on the one hand and as creative struggle on the other, of labour as an enjoyment of the rhythm of life and yet as touched by decay and dissolution, and of an instinctual contrast between creation and fabrication.

There are in fact many different words used throughout the Scriptures that we may translate as “work.” Two of the more important ones being (melâkâh) and (mal’ak); the former being used to describe God’s work in creation (Gen. 2:2-3), the latter to describe the work of artisans and craftsmen in the building of the Temple (Ex. 36:1-8) and the reconstruction of the Temple wall (Neh. 4:15-13:10).

These words are in sharp contrast to (‘itstsâbôwn) which is used specifically to describe the “painful toil” resulting from the ground being cursed at the Fall (Gen. 3:17; 5:29) and the Greek word (kopiaō), used to describe “painful” or “burdensome” work in the New Testament (Matt. 11:28).

In observing that we, in English use different words to distinguish between “toil” and “work,” Dr. Francis has suggested, in a sermon preached at St. Chad’s Church in Sunderland on Good Friday, 1996 that,

...toil is what we have to do by way of tending to life’s necessities. And since life’s necessities, like attending to our bodily needs, is based on the cycle of nature there is no lasting outcome to all our toil, since it is consumed and we have to start the process all over again. The round of visiting the supermarket is toil! But work is different, and though work may be hard and toilsome, it is productive and creative in a way in which the cyclical process of toil and labour are not. Work...is a uniquely human activity whereby we can envisage a future and work in our creative powers to construct that future. Architecture, planning, design, music, writing and all else is not labour - it is work because it expresses who we are and aspire to be, in using creatively all the materials of our life which are to hand.

Yet the distinction between that which Francis would describe as “toil” and that which he would define as “work” is not always as clearly defined in the Scriptures. There are, in fact, more generic words used in the Bible to describe work, than those specifically relating to creative activities and necessary activities, that have a more neutral connotation; such as (‘âsâh) and (ma’áseh), the latter a derivative of the former which is used throughout the book of Ecclesiastes, and its Greek equivalent (ergon), used extensively in the New Testament.

The previous paradox (mentioned by Francis) is especially evident however, in the case of the Book of Ecclesiastes, as the writer recognises the toilsome nature of manual labour, yet rejoices in its divine origins and purpose.

What does the worker gain from his toil? I have seen the burden God has laid on men. He has made everything beautiful in its time. He has also set eternity in the hearts of men; yet they cannot fathom what God has done from the beginning to end. I know that there is nothing better for men than to be happy and do good while they live. That everyone may eat and drink and find satisfaction in all his toil - this is the gift of God. (Eccl. 3:9-13)

Here the writer demonstrates a clear understanding of the “burdensome” nature of work, yet still sees intrinsic value in it. The value of work is not defined by either its creative merit, or its utility (in order to eat and drink), but in the recognition of work as being a “gift of God.” The writer sees in labour, the participation of Man in the creative process, begun by God “from the beginning” and made “beautiful in its time.” This is also implied in another Greek word used in the New Testament (kopos), which is used to describe “labour” (as in child birth), as well as one’s “labour of love” in the service of the Lord (1Thes. 1:3, Heb. 6:10).

This provides a very powerful metaphor for work as being procreative, in the sense that it is a continuation of the Lord’s work, both creatively and redemptively, whether the purpose is practical or aesthetic.

In his book entitled The Relevance of the Church (1935), F. R. Barry makes the case that,

...God is the Creator of the world, and we cannot isolate His work through Christ from His other creative and redemptive activity...the other modes of His self-disclosure. All the divine activity in the world...is at once creative and redemptive. His every disclosure to our sleeping spirits, whether on the peaks of heroic insight or the pedestrian walks of daily duty, whether in the achievement of new knowledge, in the mastery of technical skill...comes to us as summons and awakening, inviting us to communion with Himself. (p.115)

In the opinion of the researcher, a theology of work that emphasises the positive, creative, and redemptive qualities of work must be at the core of workplace ministry in a post-industrial era; especially as the nature of work itself is changing on a regular basis. In order for workers to not only survive, but also thrive, and find fulfillment in an emerging post-industrial economy, they will need to develop new paradigms for how they contribute to organisational effectiveness, relate to others around them, and integrate their lives at work with their personal lives.

The changes taking place in contemporary business are so significant that they are almost incomprehensible; the primary driver, of course, being technological advancement. Technology has always been at the heart of economic change, but never at such a breath-taking rate. It has been estimated that at the time of the Renaissance the world could expect one significant technological innovation every twenty-three years. By the time of the Industrial Revolution the rate had risen to one significant innovation per year. It is estimated that today, the world experiences one significant technological innovation every second!

That kind of innovation, coupled with other phenomena such as globalisation, deregulation, mergers and acquisitions, day (stock) trading, free trade agreements, currency rationalization and the effects of the Crash of 2008 has naturally resulted in increased competition, accelerated product obsolescence, and intense pressure on company profits and shareholder returns.

Consequently, companies have had to completely re-engineer themselves in order to compete in a highly volatile and ever changing environment. The three areas of business most significantly affected are information technology, organisational structure, and people. While the last of these (people) is obviously of greatest concern to the church, the way in which all three inter-relate is important to our understanding of how work processes will affect the very nature of work in the coming years.

The changes brought about in the area of information technology are well documented and have become an everyday part of people’s lives. Mobile telephones, fax machines, pagers, personal computers, the Internet, laptop computers, tablets, smart phones, etc. are as essential to business today as the telephone and typewriter were to the previous generation. However, their impact on business goes far beyond the obvious benefits of convenient communication. Their most significant impact is in the unleashing of the power of information.

In previous generations, information and the authority to use it was the sole domain of a relatively small group of senior executives. Information was traditionally passed down an organisation through many layers of management on an “as needed” basis. The result being that the majority of workers received very little in terms of raw data, and were merely expected to follow the instructions of supervisors. This trickle down flow of information and the hierarchy that supported it, helped to create an environment that on the one hand was secure (i.e. people knew their place and what was expected of them), but on the other hand was adversarial (i.e. labour vs. management).

The unleashing of raw information, however, has changed all of that. Now nearly every employee has access to critical information, and is being trained and empowered by organisations to use that information. Now instead of workers being told what to do and how to do it, senior executives are able to share overall business objectives with employees; and allow them to create the work processes necessary to accomplish specific goals. This shift from output to outcome has huge implications for how people work and how they interact with other workers and with management.

The combination of increased information, autonomy (in terms of authority to act upon information) and interaction among employees (often from previously disparate departments) however, has meant that the organisational structures themselves have had to change as well, in order to support the new work processes.

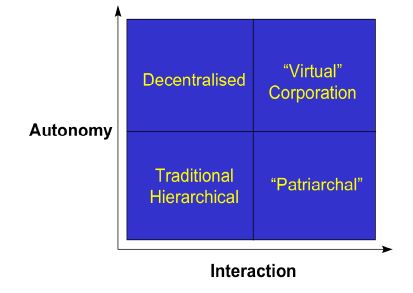

The diagram below illustrates the work process relationship between autonomy and interaction in different kinds of organisations (see Steelcase Workplace Index, 1997).

In a “traditional / hierarchical” organisation, very little autonomy is enjoyed by employees and there is little interaction among various disciplines within the organisation. In a “decentralised” company, individual employees and / or departments enjoy a lot of autonomy, but have little to do with other parts of the business. “Patriarchal” organisations allow for a great deal of interaction, but withhold autonomy, while “virtual corporations” (the model which is emerging most rapidly) embrace both concepts of autonomy (empowerment) and interaction.

Logically, if a company’s work process is moving from a “traditional / hierarchical” model toward a “virtual” model, then the structure of the organisation itself will have to move from a traditional “pyramid” shape to a more “fluid” one (as demonstrated below).

Traditional organisations are pyramid shaped, with information, power and control concentrated at the top of the organisation. Decentralised organisations have a silo shaped structure, almost as if each department or business unit were a separate company. Patriarchal companies keep control at the centre of the organisation, and are less hierarchical than traditional organisations, but keep control through strict policies and procedures. Virtual companies however, have very little structure at all, and formal policies and procedures are replaced by a common culture and shared corporate values, goals and objectives.

Radical changes of this nature in both work processes and organisational structures will naturally have a dramatic effect on the people who make up the organisations and who do the work. This is where the need for a workplace ministry will be most acute.

As Davidow and Malone put it in their book The Virtual Corporation (1992), the trauma of dramatic change itself, can have a negative effect on both employees and on companies that are reluctant to embrace it.

For some employees the experience (of change) will be more traumatic than that of the changes demanded by past industrial transformations - though the threat this time won’t be regimentation, exploitation or dehumanization but unpredictability, lack of comfortable structure, and simply too much responsibility...Workers content to put in their hours, to do the work and go home, may suddenly find themselves saddled with responsibility and control they never desired. And companies content to maintain the status quo indefinitely may not only encounter change but be forced to endure continuous, unremitting, almost unendurable transmutation. (p. 9)

In other words, change is inevitable. The question is how will businesses and their employees deal with it?

Davidow and Malone further note,

...without a doubt, the new business revolution will be a shock to the system, a blow to our sensibilities. It will require new social contracts, ever higher levels of general education, and a frightening degree of trust. (p. 19)

In fact, they maintain, “trust...is the defining feature of a virtual corporation” (p. 9). Without it, corporations will be unable to properly equip or empower employees to do the work required and achieve desired results. Likewise, employees will not be sufficiently motivated to put in the extra effort required to develop new skills, adapt to new work modes, and accept new forms of reward and recognition.

The purpose of workplace ministry in this instance is to help establish an environment of trust and provide a foundation upon which the aforementioned “new social contracts” may be built. This may be done by communicating a theology of work that evolves away from the negative view of work as curse to work as procreative; from work as profession to work as calling; from relationships as contractual to relationships as covenantal; from work as individual to work as communal; from work as temporal to work as worship.

As alluded to earlier, a high view of work must be at the centre of one’s theology of work, if that theology is going to foster positive attitudes and constructive relationships. Such an understanding of work, however, is contrary to the historic teachings of the church, which has, over the years, emphasised the “work as curse” mentality. As Pete Hammond, Director of the Marketplace Division of Inter Varsity Fellowship notes in an article from the organisation’s newsletter, Marketplace Reflection (Edition One),

For too many generations the church has taught that work is the penalty for sin. Because we have viewed work as God’s retaliation for our rebellion (ref. Gen. 3:17-19)...This terrible distortion has had devastating effects...

It is the responsibility of those involved in workplace ministry therefore, as representatives of the church in a secular setting, to combat that long held perception, and champion the idea of “work as procreation” instead.

The overwhelming biblical evidence (as suggested previously) is in support of this position. As Hammond mentions in the same article cited above,

Work is intrinsic to our nature because we are made in the likeness of God, and God is a worker. Note that when Jesus found Himself in a controversy over the Sabbath, he asserted that “My Father is always at work to this very day, and I, too, am working” (Jn. 5:17).

Indeed, God is “at work” in all of creation, and we are His fellow participants in that ongoing and ever unfolding drama of creation and redemption. As Rev’d. Michael Ranken put it, in an article for Theology magazine (March, 1982), later reproduced by Francis and Francis in Tentmaking: Perspectives on Self-supporting Ministry (1998),

In the rite of Baptism we declare that “God is the creator of all things and by the birth of children he gives to parents a share in the work and joy of creation.” He does the same thing in every other activity of life. The farmer tending the crops or animals shares in the work and joy of creation so does the canner or freezer of his produce, the supermarket assistant, the manufacturer of tyres for the tractor, the scientists testing fertilisers and the bank manager organising finance for them all. The creation they share is concrete; among other things it is part of the creation of you and me. Take the creative activity of any one of them away and we shall die, literally.

Work is essential to our very existence, and it is through our work (among other things) that the God who created us has continued to sustain us, for His purposes and to His ends. Work is central to our very beings, and it is a blessing, the fruits of which we enjoy on a daily basis. If, indeed, we hold these things to be true, then it is logical for us to take a high view of our jobs as well; and see them not in terms of their professionalism, but to appreciate each individual vocation as a calling from God. In fact, the very concept of our being called by God to certain vocations is closely linked with our understanding of God’s purposeful intent in creation and redemption. As Francis notes in the previously referenced God As Worker article,

The metaphor of God as worker, whilst it is derived from belief in God as creator, is also related to belief in God as accomplisher as the focusing of the significance of the redemptive possibility of that work (Is. 55:11). In so far as creation is itself purposive and the work of man itself creative the development of the idea of hope, and eventually of eschatology, is of relevance to the understanding of God as worker.

Addington and Graves convey a similar thought to that expressed by Francis in their work entitled, A Case For Calling (1997), where they state,

Calling is God’s personal invitation for me to work on His agenda, using the talents I’ve been given in ways that are eternally significant. To be called means I know that what I am doing is what God wants me to do. Furthermore, when I live within God’s calling, not only does my work give me a sense of meaning, but it also fits into God’s larger purpose.

Citing the Apostle Paul’s assurance that, “We know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose” (Rom. 8:28), they go on to affirm,

...work is not some arbitrary and random choice that makes no difference. Its primary objective is not to put food on the table and provide a comfortable retirement...(it) is part of God’s larger agenda in history...

To believe that our work is more than just an earthly vocation, but is part of God’s greater plan for the universe is both humbling and inspiring. It humbles those who see their jobs as especially important, when they consider their relative place in the overall scheme of things. When considered against the backdrop of time and space, even the most visible and desirable of jobs seems like a rather small cog in the machinery of God’s eschatological intent. Yet when considered as part of God’s grand design, even the most seemingly trivial aspect of one’s work takes on a whole new meaning; lifting even the mundane out of the mire of irrelevance and elevating it to a place of eternal significance and divine dignity.

Armed with the belief that all work is intrinsically important, and a conviction that the company one works for, and the fellow employees one works with are also part of God’s eternal design, workers should find establishing and maintaining “trust-based” relationships easier to do. The classic biblical model of a “trust-based” relationship, of course, and one that is central to the creation / redemption process is the covenant. As Francis states, again in the aforementioned God as Worker article,

Both redemption and faithfulness as the nature of divine activity come to expression in the idea of the covenant, and this in turn gives a particular meaning to the understanding of God’s work or action in creation itself. We may note for example how the Song of Moses at the Exodus (Ex. 15) echoes the language of the Creation story (Gen. 1.1ff). Indeed the bringing of order out of chaos (in the Genesis myth) as God’s work in creation is itself redemptive, and the redemptive purpose of God is likewise creative in the making of all things ‘new.’

We can in fact find numerous examples from the Scriptures to support the centrality of covenantal relationships as paradigms for all divinely inspired intercourse. Whether it be the Creation account (cited above), the Flood and the subsequent covenant with Noah (Gen. 9:1-17), the Abrahamic covenant (Gen. 15), the Mosaic covenant (also cited above), the Deuteronomic covenant (i.e. the “Law”), marriage covenants, or the “New Covenant” in Jesus Christ, the model of mutual fealty, trust, promise-keeping, and faithfulness are at their core.

Therefore, if one’s theology of work defines work as being a critical element in the divine plan, both as an extension of the creation process and as part of the redemption process, then relationships based upon a covenant model should, logically, be the order of the day. As Francis further states,

...the key value in human work and acting is fidelity, whereby the fulfillment of promise keeping is an inherent part of work and action, and which reflects the divine nature...this fidelity is given particular expression in Covenant, and the effect of this Covenant also lies in its dispersed relevance whereby the people are bound...under its common moral and spiritual sanction.

The concepts of “promise-keeping”, and “common moral ground” are, as we have seen, critical to the future success of companies moving away from highly structured environments and strict processes to more fluid environments and cultures held together by shared core values. In order for the efficacy of those values to be realised, however, the very nature of the relationships themselves, which bind individuals together, will logically have to evolve away from being contractual (that is to say “adversarial,” based on a presumption of violation), and become more covenantal (i.e. based on mutual interdependence, trust and an assumption of cooperation).

Such a set of assumptions may also help businesses and employees alike, view work and business activities in general, as more communal in nature than purely individualistic. In an article entitled, Some Reflections from the Perspective of Ministry in Secular Employment in the aforementioned Collected Papers, Dr. Francis contends,

...acknowledg(ing) (God) as Creator...is the very basis of our creative responsibility. And it is this creative purpose at the heart of life which should actually release us from wanting more and more in a selfish acquisitive sort of way, and which should turn us toward discovering an understanding of ‘more’ as a dimension to life which is inclusive and including-that is, an understanding of the Market in the context of community...it is the church’s particular responsibility to remind us all of the transcendent at the heart of life, our worthship, so that the inter-linking of profitability and service can be both maintained and understood.

As part of a mutually interdependent community with a set of common values, shared goals and collective responsibility for results, workers should find the move from individual to team based activities, for instance, less frightening; and a move from individual compensation to performance related “group-pay,” for example, less threatening.

Even with a sound theology of work under-girding our assumptions, changes of this nature, to the way in which we view our own contributions to organisational effectiveness, the way we relate to others, and our understanding of the relationship between one’s work and one’s worth will be challenging. However, in the opinion of the researcher, without such a foundation, adapting to the effects of a post-industrial revolution, the likes of which are beginning to emerge, will be infinitely more difficult; hence the importance of developing and communicating a sound theology of work.

Ultimately, one’s theology of work should create an ethos that promotes a view of work that recognises the ontological significance of all human endeavours; and fosters a belief that work is not merely a temporal activity, but in its purest form, is an act of worship. As Dr. Francis notes in an article entitled Church and Society in 1 Corinthians (1991), found in the previously cited Collected Papers,

...(the Apostle) Paul’s conviction...(is) that faith is that which holds worship and living in a single whole.

For the Christian, every aspect of our lives should be an act of thanksgiving and an act of worship. As the Apostle instructed the church in Colossae as well,

...whatever you do, whether in word or deed, do it all in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through him...whatever you do, work at it with all your heart, as working for the Lord...it is the Lord Christ you are serving. (Col. 3:17, 23a, 24b)

Of course, this is the ideal scenario where people will respond both intellectually and spiritually to a positive and life-affirming view of work, and allow their theology of work to help them cope in a healthy fashion with the radical changes taking place in our post-industrial age. However, as Davidow and Malone note,

...like the Industrial age before it, the emerging era has the potential to raise the quality of life for everyone to unprecedented levels...But, also like previous economic transformations, it will leave some behind - people who cannot cope with the new responsibilities, the rapid pace of change, and the demands for mental adaptability. In the frantic pace of life in this new economy...it will be easy to forget these others. A just society, a virtuous society, will tend to the needs of the disenfranchised. Thus, the last requirement of the coming business revolution is that it also exhibit the quality of mercy. (p.268)

It is the conviction of the researcher that workplace ministry has the potential to be an effective agent of mercy, not only for the aforementioned disenfranchised, but also for those who are in the midst of a transition to the new realities of our post-industrial age but who need some help in getting there smoothly.

References

Addington, Thomas and Graves, Stephen (1997) A Case For Calling, Fayetteville, Cornerstone Alliance.

Barry, F R (1931) The Relevance of Christianity, London, Nisbett.

Davidow, William and Malone, Michael (1992) The Virtual Corporation, New York, HarperCollins Publishers.

Francis, James M M (1991) ‘Church and society in 1 Corinthians: Paul as tentmaker and the church at Corinth’, Chrism, Vol. 37, pp. 14-15 (and in James M M Francis and Leslie L Francis, Tentmaking: perspectives on self-supporting ministry).

Francis, James M M (1996) Reflections on Non-Stipendiary Ministry as Ministry in Secular Employment: collected papers (1989-1996), Sunderland, University of Sunderland.

Francis, James M M and Francis, Leslie L (eds.) (1998) Tentmaking: perspectives on self-supporting ministry, Trowbridge, Cromwell Press.

Hammond, Pete (ed.) (1997) ‘Marketplace momentum keeps growing’, Inside Marketplace, Vol. 9, p. 1-2.

Ranken, Michael (1982) ‘A theology for the priest at work’, Theology, Vol. 85, pp. 108 103 (and in Francis and Francis Tentmaking: perspectives on self-supporting ministry, pp. 277-282).

Steelcase, Inc. (1997) Steelcase Workplace Index, Grand Rapids, MI, Steelcase, Inc.