The Work of a Bookseller

Blog / Produced by The High Calling

To speak of bookselling, one must first give heed to the library.

From childhood, I had read, and read, and read. When I was sixteen I was hired as a page, at my hometown’s small, but beautiful, public library. I spent my time returning loaned materials back to the shelves, keeping order to the stock.

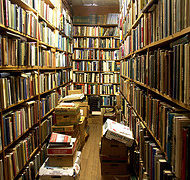

Today I remain privileged enough to spend my time with books, as a bookseller. Library and bookshop alike can feel like the friendliest, and most intimidating, buildings on the block. Where do we even begin? I sit in the center, at a desk marked Information, and gaze a panorama of titles. The bestsellers and staff recommendations alone would take any reasonable person until kingdom-come to plumb.

Self-defeating as it sounds, in the most Sisyphean way, a bookseller’s work is never done. A bookseller must know what is being sold, must have an appreciation for reading that supersedes genre boundaries, must do his best to present as comprehensive an understanding of literature’s comings and goings as humanly possible. This requires that he read— because Internet algorithms based on product sales might never demonstrate to a customer, who is languishing at the end of Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy, that another stunning example of Scandinavian crime adventure literature (published over a decade earlier) is to be found in bestselling Danish author Peter Høeg’s novel Smilla’s Sense of Snow. Nor do the algorithms tell Harry Potter fans that Susan Cooper can treat them to an equally spellbinding chronicle, The Dark is Rising Sequence.

Categorically speaking is the only way we can speak, because we understand that a love of literature is in the eye of the beholder. People have their tastes, and this is why Seattle librarian extraordinaire Nancy Pearl’s Book Lust (and for the young adult, Book Crush) is such a godsend. Herein lie the best and the brightest categorical recommendations for everything from “Physicians Writing More than Prescriptions” to “Techno-Thrillers” and “Best Business Books,” to my personal favorite “Russian Heavies.”

Pearl knows that the best way to sell a book (as one scholar might sell another on an idea or plan) is word-of-mouth, and so we booksellers attend to book reviews and press releases from newspapers, magazines, and publishing houses big and small, to titles read in classrooms, and most assuredly the local authors.

Read, research, and recommend.

I think, simply put, bookselling is work I love like none other; and, as I read, more and more, themes and subtext and threads stand out to me across genres, centuries, personalities, and political affiliations. Bookselling allows me to share some of those, but, I find, is also very much an in-pouring, like through a sieve, as customers ask me for titles and authors I've never heard of, and coworkers influence my reading habits. There is always the hunt and relief of finding the book; but, then, there are those times with the right reader who asks the right question and is open to the bookseller's insight, and: magic.

A bookseller tends a haven. Hung just inside mine is Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jane Smiley’s The Worth of a Bookstore, framed, wherein she states, “a bookstore is one of the few places where all the cantankerous, conflicting, alluring voices of the world co-exist in peace and order, and the avid reader is as free as a person can possibly be, because she is free to choose among them.” And it makes me consider what I’ve suspected since childhood: that a book is not a commodity at all, but a necessity.

Photo by Lochaven. Used with permission. Post by David Wheeler of Elliott Bay Books and author of Contingency Plans: Poems.